In the previous two blogposts in this short series, we looked at how you could start the process of finding your own unique writing voice. We established that your writing ‘voice’ is as valid as anyone’s, so long it has sufficient flow to hold a reader’s attention. You were offered some exercises to practise gaining a hold on your voice, and beginning to have confidence in it. You can find this blogpost here.

We then looked at writing in a character's voice, and how this might be different...and the same...as your own unique writing voice.

Hopefully, you're gaining that confidence as you write––whatever you write––because ‘voice’ matters whether you're engaged in poetry, fiction, nonfiction or whatever form or genre you write.You can find this blogpost here.

It might be said that the essence of a poet’s work is involved in voice. The prose writer’s decision on how the narrative voice should sound is also an essential one. Although more subtly understood, it’s important for the script writer to understand how they can employ voice in their work. Here is David Mamet (Great American Plays): The dramatic poetry (the text) must possess all the fluidity, rhythmic forces and tonal beauty of which the author is capable. This is to say it would be good if the playwright could actually write…

In Writing for TV and Radio, Teddern and Warbutten, suggest ‘voice’ is about: direct address – talking to the audience The technique of direct address is frequent in radio plays, and was employed to great effect in the US version of the TV drama House of Cards. Here is Frank Underwood, in the opening scene of the first series.

He’s bending over a dog injured by a car. After sending the only other witness to fetch help, he turns directly to the camera and says:

There are two kinds of pain. The sort of pain that makes you strong, or useless pain, the sort of pain that's only suffering. I have no patience for useless things. Moments like this require someone who will act, who will do the unpleasant thing, the necessary thing… And, looking down at the dog…There. No more pain… The voice, and what it shows us about Underwood, who has just broken the animal’s neck off screen, has our early attention.

We established that voice is closely related to pouring your thoughts into your writing, and you’ll find that your voice will be at its most confident when you write about the things you know best. ‘Write what you know’ is one of the oldest pieces of advice offered to writers, but confusion arises about this because the advice seems contradictory. Many writers create vivid pieces after researching a subject from scratch. Writers of fiction invent new worlds, or set stories in historic periods they can’t experience. How does this fit with the notion of writing only what you know?

Writing what you know means drawing on your experience, memories, knowledge and your passions. Struggling with subjects that have no interest for you will result in work that is flat and stilted. The very act of researching new ideas will be made easier if you have a sincere interest.

Style and Tone

The terms style and tone are often spoken about, especially in connection to whether a reader enjoyed a book and is talking about the voice of the author. But what are they, and how do they differ from the writer's voice? Are they something you should think about when you are writing or do they just happen? And aren’t they essentially the same thing?

Both are ways to express yourself, and serve an important purpose, while being quite different from each other.

The words, sentence structure, and grammar—the nuts and bolts of language––create your style and form the way you tell your story. One writer's style might be long, flowing sentences, other writers love sparse, short sentences. and simple, easy-to-understand words.Think about some of the authors or different genres you’ve read. Typically, each genre will have some style similarities, but each author will put his or her own touch on it.

Start by asking if your writing style fits the genre you’re writing. For instance, a crime press release should not read like a crime thriller. After all, the reader will have expectations, and veering too far off the established path can cause them to lose interest or simply be too puzzled by the disparity between theme and style to keep reading. So your first step, then, is to find the appropriate style for the genre you are writing, and make it your own.

Tone

When done well, the skilled writer can use the tone of their voice to entice the reader right into the mood – the way the writing makes you feel – of the narrator or other characters.

Exercise: Immersing in Style and Tone

Take a book by an author you admire and love to read (not necessarily contemporary). Read enough to immerse yourself in the writing style and the writer’s voice as well as the themes and forms that are characteristic of this author

Now think how you can use those skills without sounding like that writer. In other words when writing with your unique voice.

Start by being intentional – Do some research, and figure out what styles and tones can work effectively for your genre. How do you want your work to come across to the reader? Choose your style and tone before you even begin. Remember, you want to find the appropriate style and tone and then make them your own.

Also be consistent – Make sure your writing stays true to those choices or make a full change if needed, but don’t flip flop. This involves reading your work closely after you have finished, to ensure your style and tone stays consistent throughout. Inconsistencies in style and tone can leave the reader confused or annoyed.

Verbal Inventiveness

Alongside the use of sound devices such as assonance, consonance, alliteration and euphony, writers of all disciplines have the opportunity to use phono semantics, employing sounds that create a meaning in the reader’s mind. Children’s writers often take advantage of onomatopoeia, which young readers enjoy. Phonetic symbolism – the emotional use of sounds – can work for adults, but needs to be subtle. Take for instance the use of certain longer sounds, such as EE OO and SS. These are often used in the genres of horror, sci-fi and ghost stories, while GL is visual – glittering, glowing and gleaming. S can sound underhand and slippery, while STR feels strong – strong enough for words used in connection with punishment, such as strapping, striking and even strangling. To find and use sounds in this way, without the reader consciously noting your use, keep an ear open yourself, as you read.

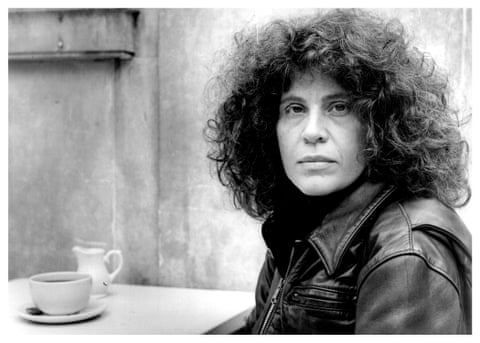

Eimear McBride uses audaciously radical and challenging language in her book A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing:

Feel the roast of it. Like sunburn. Like a hot sunstroke. Like globs dropping in. Through my hair. Spat skin with it. Blank my eyes the dazzle. Huge shatter. Me who is just new. Fallen out of the sky

Exercise Thinking about Language

- Advertising is a particular area where language is pulled apart and re-invented to help in the selling of goods and services. So copy-writers come up with new words like melty, dependability, manscaping and ‘Stoptober’, for the NHS October campaign to help smokers quit smoking.

- Choose any advertisement from any medium which attracts you because of its use of language (rather, say, than it imagery).

- Write a poem, a prose freewrite, or a very short scripted scene, using any lingual inspiration or influences you can take from the advert.

- Reflect on your use of language – whether this exercise made you think about the language you use, or if you want to experiment further with these elements – in your writing diary.