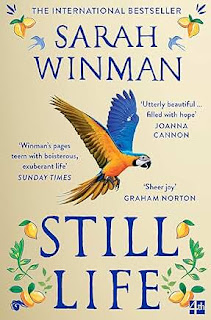

I've just finished a marvellous novel called Still Life, by Sarah Winman. In its 400+ pages, we visit Florence in the Second World War, post-war London, and Florence during the flood of 1966 and Europe at the start of the 20th century. Moving between these real events are a wide cast of characters, most of them allowing life to take them where it will, and land them wherever it pleases. In The New York Times, the main character, Ulysses Temper is described as 'a searching, wandering protagonist' but it's not just 'Temp' that wanders; the entire story behaves like a river journey. As I reached the final pages, I began to ask, 'what did Winman want to say in this novel?' The Kirkus Review notes this is ''the story of their friendship, though it is also a story of the creation of a family of friends', New York Times suggests, Does Life Imitate Art or Is It the Other Way Around? and the Independent says it is an 'exquisite testament to life, love and art.

Ulysses is a young soldier in the Allied advance in Italy in 1944 where he works with Evelyn Skinner, a 64-year-old art historian. They form a friendship bond which remain after their paths diverge, But while he's in Florence, Ulysses 'talks down' an elderly gentleman who had decided to take his own life. They go back to the man's lavish but lonely apartment, and again, a bond is formed. Meanwhile in London his soon to be ex-wife, Peg has fallen for a GI called Eddie and gives birth to a daughter she names Alys, but calls 'the kid'. Ulysses is demobbed, and goes back to working at his friend Col's pub, where Claude the blue parrot is a tavern talking point but hated by Col. The post-war decade moves on, and the novel meanders through many a story, until Ulysses hears that the person who's life he saved has bequeathed him his large apartment. He decides to go back to Florence, and asks his old mate Cress to come with him. Peg, who still yearns for Eddie and is not a good mother to Alys, persuades Temps to take 'the kid'. Cress secretes the unhappy Claude into a bag and off they all go, to live in Italy. They convert some of the inheritance into a thriving pensione. Alys soaks up the Italian life as she grows into a woman and Cress, who was able to communicate with trees in London, can also communicate with trees in Italy.

Throughout the next three decades, Ulysses continues to love Peg, Peg continues to dream of Eddie, Cress finds Italian love in his golden years, and Alys finds love with another teen girl. Ulysses goes back to creating globes of the world, and in this way, is crazily linked back to Evelyn, who keeps an eye open for her old war friend, but constantly misses him until, one day, they find themselves all together; now a largish group of young and old, English and Italian.

The story, then is a winding route, just like a river. I loved it but immediately thought; 'I don't write like this; I couldn't plot like this'. I'm a bit of a plot junkie; Winman is clearly a 'characterphile'. (I created these terms to describe different 'kinds' of plotter; you can read about them here.)When I start a book, I'm usually inspired by landscape, my first point of inspiration. In my Shaman Mystery series a walk, years ago, through the Somerset Levels, sparked my interest in the area, followed by a distant, then closer, then close view of the Hinkley Power Station, which is featured in On the Gallows. Landscapes do it for me, but there are many other starting points.

Louise Doughty makes a similar point in her article, Taking a Line for a Walk (Mslexia No 99). 'My most recent book', she says, 'arrived – like Apple Tree Yard and Platform Seven before it – with a strong visual image'. She then takes that image 'for a walk', asking questions of it, until she has a scene, 'followed by a scene showing what happens next on the journey...until I worked it out, some 100,000 words later.'This is a great way to write a novel if you are a 'characterphile'. If however you are a 'plot junkie' the idea might fill you with horror! What, no chapter by chapter outline, no timeline, to plot points to lead you on? I'm a plot junkie, but I'm quite tempted to have a go at this meandering method, the next time such an image, or landscape, enters my mind. Or, as happened this time to Doughty, a line comes to you, out of the blue. The same questions can be asked of this line or phrase or sentence, the same walk take, until, chapter upon chapter, you find an answer.

Doughty talks about how the 'synapses in your brain are prompted to join up by something'. She doesn't go on to say what that 'something' is, but I would suggest we go back to the Ancient Greeks, who personified the inspirations that arise from intuition, or 'synapses' if you like, as Muses. The nine daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, or Memory, the Muses prompt those they visit to remember what they have forgotten. Muses with a special affinity for writers are:

Calliope, the Muse of epic poetry

|

| courtesy of Wikipedia |

Euterpe, the Muse of lyric poetry

Melpomene, the Muse of tragedy

Erato, the Muse of love poetry

Polyhymnia, the Muse of sacred poetry, and

Thalia, the Muse of comedy

Sadly, there isn't a Muse for short stories, as these weren't around in ancient Greece. Their stories were narrated orally, or dramatically, and poetry was used in both forms, especially as it helps with memory...Mnemosyne…when retelling a story!

Like Doughty, one should never sit around and wait for a muse to visit, in the hope she'll just 'show up'. She should be seduced to come to you. Doughty had gone to Amsterdam, 'wandering around the city for a week...with an empty notebook...' in the hope that she would 'encounter my next book'. She was seducing her Muse, and finally, was obliged. 'What do you do when you're in the tase of creativity that I might as well call 'pre-technique', where all your struggles for plot construction or character development are useless because you don't have the foggiest idea what you book is about?' Suddenly a line came to Doughty. The opening line to a story she didn't yet know. The Muse had descended. She could begin.

It seems a bit extreme to visit a different country in order to find your Muse, but you should be on the alert at all times. When your muse pops in every so often to drop a story idea on you, sit up and pay attention.

When you have a story idea, write it down in a journal or notebook. You can't write every story right away, so put it in the pickling juice and go on. Also remember the wonderful 'Muse-filled' Miscellany File, or Commonplace Book, which I talk about here. Read, look through your ideas from time to time, crossing out the ones that have lost their muster. Also cross out the ones that seem too cumbersome. Keep the simple ideas and the ones that give you chills in your spine. Maintain this practice and you'll find that you always have a few good story ideas in the queue.