|

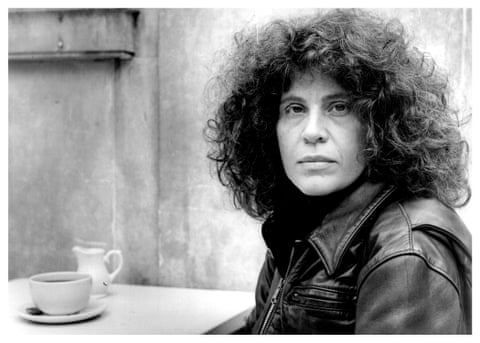

| Anne Michaels |

Michaels must be one of the few writers today who can pull off writing in fragments, for fugitive pieces could as easily serve as the title of this new book, Held, a novel similarly made up of scraps of storytelling and essayistic fragments, and the themes of memory, war, and personal ghosts, revisit her preoccupations. But this book not about the Holocaust, but of many wars and war zones, and the relationship of the characters to these.

I first read the Canadian novelist and poet Anne Michaels when her 1996 first novel, the multi-award-winning Fugitive Pieces, after it won the Orange Prize for Fiction.The story is divided into two sections––Jakob Beer is a Polish Holocaust survivor––while Ben is the son of two Holocaust survivors.

The themes relate to the Holocaust––trauma, grief, loss and memory which are explored thought nature metaphors. The story has a poetic style, which has caused some critics to feel that it re-imagines the 'story' of the Holocaust, partly through nature.

The Booker Prize judges said some very nice things about this book;

‘There are very few books that can achieve a pitch of poetic intensity sustained across a whole novel. Through broken stanza-like paragraphs and chapters that move between different members of the family across a century, Held achieves the feat of being deeply moving and asks the question ‘Who can say what happens when we are remembered?’ with tenderness.'

‘We loved the quietness of this book: we surrendered to it. The large themes are of the instability of the past and memory, but it works on a cellular level due to the astonishing beauty of the details. Whether it is the mistakes that are knitted into a sweater so that a drowned sailor can be identified, or the rituals of making homecoming pancakes, or what it feels like to be scrutinised as you are painted, the novel makes us pause.’

We are carried back and forth in time. Each section introduces new characters, different settings.here are quite a lot of characters within the book and one thing I tried to do was tie them all together; it seems that most of them are related to the others, but often it's quite hard to find that relationships through the generations as we move from the First World War to out own times, and the wars most recently remembered. Anyway, here goes; perhaps this will help you pin down the elusive butterfly that is this absorbing read:

John is a soldier who returns to his wife after being injured during the First World War. As he attempts to come to terms with the psychological trauma of his experiences, he finds works as a photographer.

Helena is John’s wife, a talented artist who constantly doubts her own talent and supports John as he struggles with the vivid memories of his experiences during the war.

Anna is John and Helena’s daughter; her work as a doctor means she frequently leaves her family to work in war zones.

Maria inherited the same caring nature as her mother, Anna, and also becomes a doctor, and is similarly drawn to working in war-torn areas.

Working through the characters and the dates, I began to pick up echoes and piece together the tenuous personal links which hold together the disparate stories, first understanding that Aimo, who meets another Anna in Finland in 2025 must be the child whose musician parents we saw being expelled from Estonia for thought crimes in 1980, and then deciding that when we meet a Frenchwoman, out collecting firewood in1902, falls briefly for a photographer, their baby will become John. But there are also links which work though the themes, and it felt to me that these are meant to be even stronger becoming the point of the story, so that the characters are the carriers of theme and idea, posing profound questions about the human state, all expressed in Michael's arresting prose.

This makes her writing sometimes very difficult, but also so absorbing to read. What I loved most (even better than trying to piece it all together) are the little snapshots which are often hugely affecting, suffused with an awful, aching yearning for what is lost. It demands thought and concentration from its readers but more than repays them. Here, Mara, back from being a medic at the front of a war, remembers some experiences:

She told them about her friend, a nurse who had more experience and compassion in her hands than Mara felt she would ever have…this same nurse had ridden through a bicycle through the dark, no light to give her away, packets of medicine taped to her skin under her waistband, who plummeted into an abyss that had not been there only hours before. The father who kept a scrap of cloth tied with string around her neck, fill with teeth, proof his sone had existed, though Mara knew he would never be sure they were his son's.

However, I must admit there are critics of this kind of writing; this style of novel. Bikerbuddy, online, said; 'I’ve never read Anne Michaels before. Polarising books can be interesting and I was interested in why this book had such a range of reactions with the public. Some loved the language and sentiments of the novel, others thought it pretentious, opaque, overwritten and/or confused. For my own part, I enjoyed aspects of the broad story,I felt as I read, it is a novel about an idea, as many are. But unlike many great novels which allow the reader space to ponder and reflect, Held felt like an act of proselytising. It’s a thesis dressed up in people’s clothing, walking and talking, with a determined purpose. This is an aspect of the book I disliked, yet I have found that others have been drawn to it. Held was different for me. It felt like a manipulative book. It felt dishonest.

The Times Literary Supplement said; The lush, lyrical prose favoured by the likes of Anne Michaels…is a risky business. At best it brings intensity, inwardness, descriptive beauty and a relief from the thudding and-then-and-then of conventional storytelling; at worst it can result in vatic waffle. In either case the impulse is to suppress definite characterization, historic specificity and narrative momentum in favour of “poetic” evocation.

Anna Bonnet says; This Canadian novelist, who won the Women’s Prize in 1997 for her Holocaust novel, Fugitive Pieces, is also a poet and it shows: Held is told in tiny, poetic vignettes. For me, this was part of the problem. While there are some mesmerising lines in this book, it is all so fragmented that I struggled to follow the narrative thread, let alone care for the characters.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Leave a comment about this blog!