In her website Yael Van Der Wouden introduces herself as A great smalltalker... available as a +1 for your cousin's wedding. Woulden also keeps a blog, Dear David: An Advice Column, in which Sir David Attenborough speaks about the natural world in answer to writers' problems. It's funny and clever in a similar way that The Safekeep is funny and clever. And yet her 2018 essay, On (Not) Reading Anne Frank suggests that The Safekeep is also a darkened polemic on the Dutch position after the 2nd WW.

In her Booker interview, she explains the moment that this book came into her mind, starting with… a fascination with how the Dutch narrativise national histories; my obsession with homes and the fantasy of owning a home; wanting to explore desire as the flipside of repulsion. The way it happened was like this: I was in the car on the way back from a funeral, looking out over flat Dutch fields, and somewhere between grief and a need to escape the idea bloomed, of a house, a woman and a stranger.

A house, a youngish woman, her two siblings and a stranger.

It is Holland in the 60's and Isabel lives alone in the family home, weighed down with duty left by her dead parents, avoiding contact with humans, hating most of the people she knows: Louis, who will be gifted the house once he marries (and he’s in no hurry to stop moving through pretty girls like his latest, Eva): and Hendrick, who lives with Sebastian, a person Isabel particularly turns her face from in shame

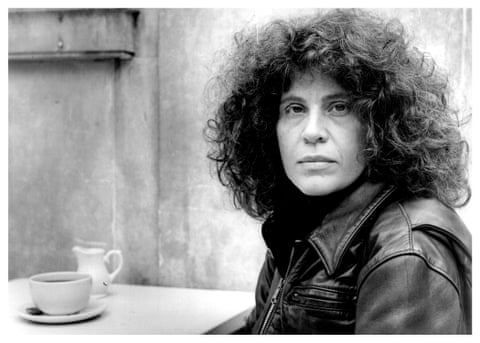

![Author Yael Van Der Wouden]() .

.

This book did not win the Booker Prize. So maybe you won’t want your book to be––suddenly and surprisingly-–this sexy, with intense emotion and fiery physicality… Isabel could see herself from the dresser mirror: face red, mouth like a violence.

Wouden admits––erotica is about the knife’s edge of voyeurism and participation. As a reader, you want to feel like you are present, but if you are too present then I think the text tries to envelope you, tries to comfort, and I think good erotic writing makes you a little uncomfortable.

You might not want your novel to be in the 1st person perspective of a repressed, unlikeable woman such as Isabel, without being able to show that vulnerability that hides behind such a front. And, in 1st person, how can the story reveal what happened almost 20 years previously? Two-thirds of the way through, after the central explosion of love and lust, we reach The Diary. Diaries don’t often work in modern novels, but this one, stolen by Isabel after a caustic row with her lover, reveals the darkest sides of wartime Europe.

Think about taking an extended symbol throughout the book, as Wouden does. In the opening lines, Isobel finds broken pottery in the garden. It's a shard from the china plates her mother loved, and which she now keeps locked away. She knows one has never broken, but if that is so, how could this shard be in the garden? The answer dogs her throughout the novel, and it is not until we read the diary that we know the shocking answer.

You might like to be in Wouden's position,however, of having her debut novel snapped up by Penguin after a bidding war.

What did the English reviewers say about this debut? The Observer says that the author weaves this story of historical reckoning (or its avoidance) with an account of Isabel's individual and sexual awakening,

The Guardian's reviewer said The book's powerful final act provides an already weighty emotional situation with an extra layer of historical heft.

Reviewer Anne Bonnet loved it; The Safekeep is simmering and sexy, but it is also a Trojan horse of a novel. Not much is, rightly, given away in the synopsis and it is only in the last third that you realise you have been reading a very different book…

Perhaps for me, the ending wasn’t quite perfect. But that might be because whatever way the final moments of such a twisted the story might go, I’ll have wanted it to go in the other direction. Happier? Darker? I’ll let you read it and make up your own minds.