Yes, Doctor Zhivago, the film.

Five years later I bought a two-volume edition of the book and started the long journey though those landscapes, that love story, that awful bloodshed. Yesterday, fifty years on, I finally came to the last page in Pasternak’s book. As I did so, my illusion lifted.

For all those years of faltering, stopping and restarting at the beginning of the book yet again…I understood and presumed that Doctor Zhivago was a real person.

It was clear to me that the book was biography. I was unable to come to terms with the idea that anyone could invent such an epic tale – starting at the time of the last Tzar and documenting the revolutions of 1905 ad 1917, finishing in the days of the 2nd World War. Surely such an expansive boundless tale was based in some truth? Surely Pasternak had researched the real, if slightly forgotten, life of a Moscow doctor?

|

| Hum along as you read |

I’m a novelist myself, always on the lookout for characters and ideas, but not for one moment did it occur to me that Pasternak had made those life-sharp characters up….Yuri and his gracious wife Tonia…Lara and her idealistic, ruthless husband Pasha Antipode…the evil Viktor Komarovsky and the shadowy figure of Yuri's half-brother, General Yevgraf Zhivago.

But of course Doctor Zhivago is a work of fiction. It’s not even Pasternak's first work of fiction, although most of his writing is poetry. Of course, he made it all up!

Or did he?

|

| Pasternak's sister, Anna, wrote a book about Olga |

Of course all novelists are inspired by the love they themselves feel – all loved ones are the most ‘special’ of people. Olga Ivinskaya was a poet, a clever and compassionate person and I like to think that their deep love, and their terrible parting, galvanised Pasternak to write his greatest work. Doctor Zhivago was smuggled to Europe by an Italian journalist and published in Milan in 1957.

|

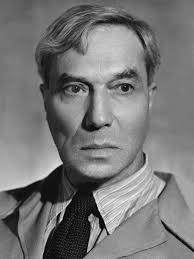

| Boris Pasternak |

One of the most romantic aspects of the book is the way Zhivago journeys through the vast landscapes of Russia. After serving in the First World War, the Zhivago family leave communist Moscow for the Ural Mountains, where, Tonia is pregnant with their second child and Yuri begins an affair with Lara. Zhivago is forced to join a partisan army fighting the Tsarist Whites, but he escapes, walking through the snows to Yuriatin, where Lara lives.

Pasternak’s intent was to interconnect Zhivago to as many of the Russian people as he could. Like his inventor, Zhivago’s gentle and artistic character makes him vulnerable to the brutality and harshness of the Bolsheviks. He is unable to take control of his fate, and dies in utter poverty. leaving poems as his legacy.

Doctor Zhivago is not an easy read, but it is a heady and rewarding one.

Wikipedia sums it up when it says; The plot of Doctor Zhivago is long and intricate. It can be difficult to follow for two reasons. First, Pasternak employs many characters, who interact with each other throughout the book in unpredictable ways. Secondly, he frequently introduces a character by one of his/her three names, then subsequently refers to that character by another of the three names or a nickname, without expressly stating that he is referring to the same character.

Oh, ye gods, those names are sooo hard. This Wiki character map shows what that really means for the reader;

But I do like to complete a work of classical literature every year, and 2000 was a great year to be reading this complex but breathtaking book. I started again at the beginning once more, and I kept going…until I reached the end of the story.

I felt fantastic. I’d read this book, described as ‘the first work of genius to come out of Russia since the revolution’ (V.S. Pritchett). I'd loved every word of brilliant prose...

…But the sun sparkled on the blinding whiteness and Yury cut clean slices out of the snow, starting landslides of dry diamond fires. It reminded him of his childhood. He saw himself in their yard at home, dressed in a braided hood and black sheepskin fastened with hooks and eyes sewn into the curly fleece, cutting the same dazzling snow into cubes and pyramids and cream buns and fortresses and cave cities. Life had had a splendid taste in those far-off days, everything had been feast for the stomach!

In 1958, Boris Pasternak won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Six days later, under pressure from the Soviet Union, he sent a telegram: "Considering the meaning this award has been given in the society to which I belong, I must reject this undeserved prize which has been presented to me. Please do not receive my voluntary rejection with displeasure.” Pasternak’s poetry, plays, and translations were well known in the USSR but Stalin’s government had threatened, suppressed, and spied on him. Doctor Zhivago was never published in the Soviet Union.

|

| Alec Guinness as Yevgraf Zhivago and Rita Tushingham as Tanya |

It is the ending of the story that is most surreal and puzzling…most of which is absent from David Lean’s 1965 film version. After Yury has tricked Lara into taking her daughter and going away with her previous abuser, Komarovsky, he returns to Moscow and begins living with Marina, and they have two children. On the way to his first day’s work at a Moscow hospital, he dies of a heart attack. Lara comes to the funeral and asks Yury's half-brother if there is any way to track the location of a child given away to strangers. She stays for several days and then disappears, likely dying in a concentration camp. Years later, Misha and Nicky are fighting in World War II and encounter a laundry-girl, Tanya, who tells them her life story. They determine that she is the daughter of Lara and Yury. And that is how the story ends, except of course, there are pages of the poetry of Pasternak, writing as Zhivago. These straggling, strangely plotted final sections only consolidated my idea that all this must be true. It felt too raw, too human and, to a degree, too far a coincidence. I could see the reality of the lonely man seeking solace, already sick at heart and shameful that his wife and first two children now live in Paris. It felt painfully true.

Doctor Zhivago is mind-widening and lyrical. Beautiful prose and strange, eloquent dialogue. Descriptions of the huge landscapes of Russia, and a story that documents its turbulent twentieth century. If you've never read it, you can do so here, in an excellent translation (Pevear and Volokhonsky).