|

| Copyright New Yorker |

| |

|

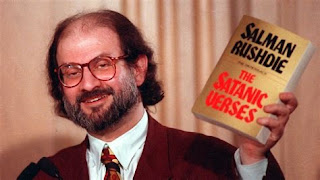

Having loved Midnight's Children, which was his second novel, I couldn't wait to read The Satanic Verses when it came out in 1988. This is the story of two Muslims confused by the temptations of the west. The first returns to his cultural roots. The other, intellectually unable to return to the faith, finally kills himself. I loved it. One of its themes is the way immegrants are treated in the UK and another looks at the very foundations of Islam.

As I read, it was being burnt. Despite the fact, that to me, a westener, I couldn't see any content that seemed to denounce or critique the faith of Islam, Muslims had many issues with the book, including the story, the title, and some of the names used. In December 1988, around 7,000 Muslims in Bolton held a peaceful protest where they burnt a copy of the book. The Ayatollah Khomeini, leader of Iran, announced a Fatwa was on 14th February 1989.

Could Rushdie have expected this reaction?

Writers stick out their necks. By the nature of being able, especially via fictional works, to say anything about anything, they constantly fall foul of current morals, ethics and the law. Of course, it’s wise not to be disrespectful, especially without researching and understanding your chosen subject. On the other hand, remaining neutral and inoffensive generally results in bland, insubstantial writing.

An attempt at a private prosecution to get The Satanic Verses banned was unsuccessful, in fact, the Home Office announced it would not allow any further blasphemy prosecutions.

Martin Amis, who interviewed Rushdie, suggests… a Fatwa is at once a death sentence and a life sentence. In his own phrase, Rushdie is firmly ‘handcuffed to history’. He is neither a god nor a devil; he is just a writer – comical and protean, ironical and ardent…I bought an evening paper. Its banner headline read: EXECUTE RUSHDIE ORDERS THE AYATOLLAH. Salman had disappeared into the world of block caps. He had vanished into the front page…His uniqueness is the measure of his stoicism. Because no one else – certainly no other writer – could have survived so well…. Amis interviewed Salman in September of the same year, at a Mystery Location…‘When I first heard the news, I thought: I’m a dead man. You know: that’s it. One day. Two days’… (Visiting Mrs Nabokov, Penguin Books 1993 pg 172)

After a failed assassination attempt in 1989, Rushdie began came out of hiding and soon became a central figure in debates on free speech and censorship. In 2007 he received a knighthood for services to literature and by then, was in public more and more.

On 12 August 2022, he was about to start a lecture in New York, when man rushed onto the stage and stabbed him repeatedly, including in the face, neck and abdomen. Rushdie was airlifted to a trauma centre and underwent surgery. Only one day later, he was taken off the ventilator and was able to speak. He had lost sight in one eye and the use of one hand but survived the murder attempt and was soon writing a memoir about the attack, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, which hit number one in the Sunday Times Bestsellers List straight away.

Perhaps the most Rushdiean part of this awful event was the fact he reported remembering a vivid dream, in which he was stabbed in a Roman amphitheatre, only two days before the actual stabbing occurred. The intensity of the dream caused him to consider canceling the event–but he eventually decided on attending.

She is still a young woman when the magic begins. Pampa instructs two of her brothers, Hukka and Bukka, to sow a bag of seeds at the site of their old village. A city grows, and people sprout from the earth. Pampa whispers memories into them, so they feel they have a history. The brothers become the first kings. Pampa marries them each in turn, though her daughters are born of her true love, a Portuguese horse trader who names the city Bisnaga.

The city she founds becomes a utopia—a feminist one–Pampa is an avid advocate for gender equality, and wishes her daughters to rein after her husbands’ deaths. This request is met with much conflict and her sons seize control of the kingdom. Pampa and her three daughters are forced to flee into a magical forest where they shelter for several decades. The three daughters eventually grow in separate directions and Pampa returns to Bisnaga. In her absence, she had become a legend, and, as she still looks much the same age, can move about the city freely. Eventually, she becomes the advisor of the latest monarch, Krishnadevaraya.

After many wars to guard and widen the borders of the kingdom, Krishnadevaraya goes mad and Pampa, caught in one of his rages, is forcefully blinded with an iron-rod. She takes up refuge with a holy man, finally beginning to feel her age which is now over two hundred. The residents of the city become outraged at this betrayal and turn against their king and the kingdom degenerates and is ransacked and destroyed. The novel ends with Pampa burying her written history in a pot and waiting for the Goddess to release her so that she may die.

So what is this allegory about? It is possible that he has used an ancient empire, the Vijayanagara, and to a degree followed major turning points in the history of the empire. But it strikes me we could actually be following major turning points of human history. Even so, there are moments that need careful analysis; for instance the invasion of the pink monkeys in the forests where Pampa and her daughters have settled. Who are the conniving pink monkeys who inveigle their way into the monkey tribes and then take them over? Maybe that is what human history was: the brief illusion of happy victories set in a long continuum of bitter, disillusioning defeats (pg 155).

And why, when she takes refuge in a cave with a holy man after her mother’s death, is she regularly abused by him? This passage struck me: That's how men were, Pampa Kampana thought. A man philosophized about peace but in his treatment of the helpless girl sleeping in his cave, his deeds were not inlignment with his philospopy.

|

| Virupaksha Temple, Vijayanagara, Karnataka |

In some ways, Pampa could almost be Salman, who has experienced both adoration and opprobrium for his acts of creation. Without doubt, to me, the writer is saying that we humans are both good and evil. In this book we meet oppression, religious zealotry, authoritarianism, divide, patriarchy. But there is also equality, redemption, the power of love, and a demonstration of how humans can be at their most creative when they live in an atmosphere of openness, tolerance, and egalitarianism.

The 'Stellar Author' series of posts on Kitchen Table Writers has looked at several amazing writers, including:

Just click on the link to read the blogs.