- The tombs were accessed via rectangular vertical shafts dug deep into the earth, a method originating from the bronze age. Lady Dai's funnel-like crypt contained more than 1,000 precious artefacts, including makeup, toiletries, lacquerware, and 162 carved wooden figures which represented her staff of servants. A meal was even laid out to be enjoyed by the 50 year-old duchess in the afterlife. In the central area lay three nesting coffins. Inside many layers of silk was the beautifully preserved mummy, wrapped in her finest robe, her skin still soft to the touch. The fact that she was quite corpulent, from her amazingly rich diet – scorpion soup was apparently a favourite – may have helped the quality of her ancient skin.

An artefact found in the tomb - The outermost coffin was a plain box. Inside were the three nesting coffins painted with hugely expensive lacquer in black, red, and white. This protected from water damage and bacterial invasion. I cannot imagine how awed the archeologists must have been as they steadily revealed each coffin.

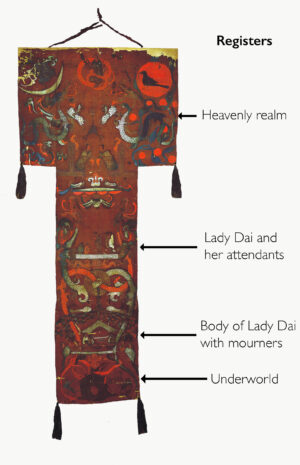

- But even more magnificent than all of this, was the banner that lay on top of the innermost of the coffins. This almost intact piece of beautifully painted silk would have been part of the procession of the Marquise to her resting place. And on it were full and intricate instructions for her soul. The banner instructed Xin Zhui's spirit how to reach her paradise.

- This T-shaped silk banner was over six feet long and in excellent condition for 2000-year-old fabric. It is a very early example of pictorial art in China.

- I first encountered this breathtaking story of life in Ancient China at a lecture given at Lampeter University, in West Wales. Fabric specialist had travelled from across the country to learn more about Lady Dai’s banner, its art and its messages.

- The banner is divided into four horizontal sections. In the first, Lady Dai is pictured standing on a platform, leaning on a staff, wearing an embroidered silk robe. Framing the scene are white and pink sinuous dragons, their bodies looping through a 'bi' (a disc with a hole, representing the sky). This section is remarkable in itself, as it is the earliest example of a painted portrait of a specific individual in China.

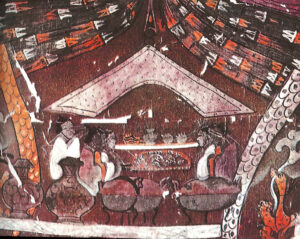

- In the section below this scene, sacrificial funerary rituals are portrayed in a mourning hall. Tripod containers and vase-shaped vessels for offering food and wine stand in the foreground. In the middle ground, seated mourners line up in two rows.

- On a mound in the between two rows of mourners there are the patterns on the silk that match the robe Lady Dai wears in the scene above this.

- Lady Dai’s banner helps the modern world understand the religion she followed two millennia ago, and how artists began to represent depth and space in early Chinese painting. They made efforts to indicate depth through the use of the overlapping bodies of the mourners. They also made objects in the foreground larger, and objects in the background smaller, to create that illusion of space.

- Above and below the scenes of Lady Dai and the mourning hall, are images of heaven and the underworld. Toward the top, near the cross of the “T,” two men face each other and guard the gate to the heavenly realm. Directly above the two men, at the very top of the banner, is a deity with a human head and a dragon body.

- Dragons and other immortal being look down from the sky to a toad standing on a crescent moon flanks the dragon/human deity and what looks like a three-legged crow within a pink sun. The moon and the sun are emblematic of a supernatural realm above the human world. In the lower register, beneath the mourning hall, the underworld is painted with a red snake, a pair of blue goats, and an earthly deity, holding up the floor of the mourning hall Two giant black fish cross to form a circle beneath him. The beings in the underworld symbolize water and earth, and they indicate an underground domain below the human world.

- While other mummies tend to crumble at the slightest movement, Dai is the most well-preserved ancient corpse yet to be discovered. Unlike most of the mummies found in ancient Egypt, her organs were all intact – there was still blood in her veins—Type A. This allowed pathologists the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to perform an autopsy on the preserved body, 2,100 years after her death, ultimately giving us a firsthand glimpse at how the richest of the rich lived during the Han Dynast and is arguably the most complete medical profile ever compiled on an ancient individual.

- Thanks to her luxurious lifestyle, the Marquise had osteoporosis, arteriosclerosis, gallstones, liver disease, diabetes, and high cholesterol. She must have been in pretty constant pain from a fused spinal disc.

- Immediately after she was exposed to oxygen for the first time in 2,000 years, her body started to break down, which caused some of the visible decay apparent in the photograp of her mummy at the top of this blog. Her body and belongings were taken into the care of the Hunan Museum, where she now lies in state.

|

| Xin Zhui, (better known as the Lady Dai) |

|

| The outside cavity holding the three coffins |

|

| One of the three inner caskets |